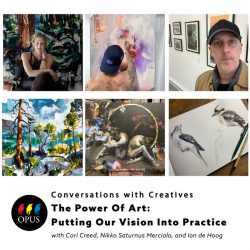

The Power Of Art : Putting Our Vision Into Practice

February 17, 2022We’re currently discussing The Power Of Art. Last month, we kicked things off by Imagining Endless Possibilities, and this time we’re discussing Putting Our Vision into Practice.

If we will what we imagine and we create what we will, what does it take to develop our vision, especially when contending with a constantly evolving reality? Can daily practice and routine ground us? What other tips can artists provide to help us navigate such rapid change?

Cori Creed

Cori Creed is an established West Coast Canadian painter who captures the drama and emotion of coastal landscapes, by immersing herself and viewers in the spontaneity and unpredictability of nature. Born in Vancouver, Cori studied Fine Art at Simon Fraser University and Design at Capilano College. Her work has been placed in various private and corporate collections across Canada. She lives and paints out of her home and studio in West Vancouver and has been represented by Bau-Xi Gallery since 2011.

I work quite large so most of my work is done in the studio. Everything I see becomes an inspiration – generally out walking around or climbing and taking photos. I start with that material but also things I may’ve been thinking out that day or other artists’ work. I might be drawn to some colours in an abstract way and something about those colours and in the subject I’m looking at pushes me.

Nobody really sees things the same way. They’re viewing the world through layers and layers of filters stemming from their experience, not seeing the piece in the way you’re presenting it.

One show I did with a couple of artists looked at the way we consume and create our identity with material things. I used photography and created a series of large banners. In those kinds of exhibits, I’m really thinking hard about, ‘How can I get this message across to someone?’ In my painting, I’m more thinking about telling my story and communicating the way I felt in that place.

The one way I try to interact with the viewer is with the difference between the story and the storytelling. I create a three-dimensional space or stage set and that’s the story, but I also try to use marks that live on the surface and disrupt that illusion. I want the viewer to think back and forth between the physical nature of painting and the mark making of storytelling, as well as just trying to find something interesting in a landscape.

I feel change is integral to art. Being pushed in different directions can bring growth, and flexibility is key.

My best work happens quickly and I almost don’t remember doing it. That’s what I chase. How can I get myself into this flow state in painting where things are almost automatic? The best way for me to do that is to put on an audiobook that just removes the chatter part of my brain and allows me to focus on the almost unconscious act of painting.

Even if you’re not inspired some days, just start. There are times where you’ll end up throwing out half of it, but you’re learning, you’re growing, and you can’t look at it as a waste.

Nikko Saturnus Mercialo

FREDRIX Ambassador Nikko Saturnus Mercialo is a visual artist, writer and designer whose creative production spans traditional and digital techniques of painting and sculpture, infusing classic motifs with his own dark and energised spirit. The subjects are symbolic representations of hidden truth that finds its way back through darkness to the light.

I’ve been a professional artist for four years, basically the equivalent of going to art school. This period has been very much about experimentation – trying to feel my way through what I’m trying to do as a human being, what I’m trying to contribute as a man, and what I’m trying to do as an artist and how that’s going to be affecting the culture that I am both creating and being created by.

I try to focus on classical themes – the same sorts of subjects that have always moved humanity forward, as well as the tidal sweep of human emotion in a world that’s really beautiful and brutal.

Most of the experiences we have that are profound enough to be worth painting exist in a dichotomy. You’ve got raw power and vulnerability, longing and loneliness, memory and moment – all of these different emotional states and different cultural contexts all mixed together. So I usually start from the perspective of feeling the emotion of the piece and what I’m trying to say through that.

Yes, we’re living in turbulent times but we’ve always lived in times of change. All we have to do is look back in history to see how many times people thought the sky was falling and the world was ending but it didn’t – we’re all still here. The difference now is that we see it all and it’s changing quickly. We’ve developed this sense of alienation through technology that ironically none of us can live without. The interesting thing is, being able to face all those challenges provides very fertile soil for creative imagination. All greatness has its roots in sorrow.

I don’t think there’s anything really glamorous about creative practice. A lot of people try to dress it up but at the end of the day, it’s just hard work – filling sketchbooks, trying new techniques and having the discipline to be comfortable not being good at something until you are good at it.

My daily practice just looks like puritanical discipline. I don’t really have any secret tricks. Everybody looks for a life hack these days to try and shortcut expertise and find a quick way up the mountain. But it’s the journey that creates it. Daily practice would be my advice to any younger artists or anyone who’s picking up art for the first time – do it every day, even the days you don’t want to. Especially those days!

Ian de Hoog

Ian de Hoog is a Canadian watercolourist and instructor whose creative career began via photography, and it was during a brief stint studying architecture that a physical love of painting manifested. While primarily self-taught, Ian’s paintings have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions and are included in a growing number of private collections around the world.

Most of what I do, if not all my paintings, are based upon some form of a reference. This is where the photography background comes in handy. I’m no esteemed National Geographic level wildlife photographer but when the end is a painting I’m just looking for interesting poses and maybe a little bit of a colour reference as a starting point.

Watercolour as a medium is unpredictable at times and that is one of the things I really like about it. There are things that I can control and there are things that I can’t. I could take the same painting and repeat it a number of times and never end up with the exact same thing.

I can be prone to getting stuck into the details and that fights a bit with what I like in a watercolour painting – generally something looser. I always have this conflict where my eye goes to all the little things but my heart just wants to abandon them and start splashing paint around. Trying to find a balance of those two, I’ve had to come about a process that gives me a concrete way of looking at a subject – figuring out what I’m going to do to move forward, whilst still having some room to relax a bit so I don’t have to worry so much about the details.

I’ll look at a reference and go, ‘What is the overall feeling of the hue I am seeing? What are the basic qualities?’ I really just try to narrow it down to what strikes me and then I don’t go back to the reference so much. That frees me up quite a bit.

Ultimately I like a process that has enough space in it, and where I get to continue to explore new ideas, different techniques and maybe a different way of seeing colour. Having a process that is reliable and repeatable has given me a lot of confidence. As long as I trust what I know has worked in the past, what I’m doing should end up with a result that, greater than 50% of the time, I’m going to be pleased with.

Sometimes we have a notion that we need to see a significant increase in capability and output or it’s not worthwhile, but you’re going to get a lot more out of daily incremental progression. If I can just find five minutes for a gesture drawing or a continuous line drawing, it’s going to [help me progress].